In the Gospel attributed to Mark, a group of named women anchor the narrative from Jesus’ death until the end. The narrative follows them. The males who had followed Jesus have fled and never reappear in the narrative. The women become the reader’s sole support.

Their introduction is abrupt. Immediately after the centurion’s ambiguous declaration, the narrator immediately introduces the women. “Now some women were observing from a distance, among whom were Mary of Magdala, and Mary the mother of James the younger and Joses, and Salome” (15:40). The names on the list vary, but Mary Magdalene is always first.

Then the narrator comments how “these women had regularly followed and assisted him when he was in Galilee, along with many other women who had come up to Jerusalem in his company” (15:41). This abrupt introduction impels a reader/audience to re-evaluate the whole story. The women have been present all the time but not seen.

At the end of Jesus’ burial, the narrator again notes the women’s presence. “And Mary of Magdala and Mary the mother of Joses noted where he had been laid to rest” (15:47). In the very next line, the named women are present at the tomb. “And when the Sabbath was over, Mary of Magdala and Mary the mother of James and Salome bought spices so they could go and anoint him” (16:1). In modern translations, these two sentences appear in different chapters, but ancient Greek gospels had neither chapters nor verses. The names would be rapidly repeated, thus giving them prominence. The narrative reinforces who are the witnesses to Jesus’ death, burial, and the empty tomb—the women! The women—Mary Magdalene, the other named women—are the tradition’s source.

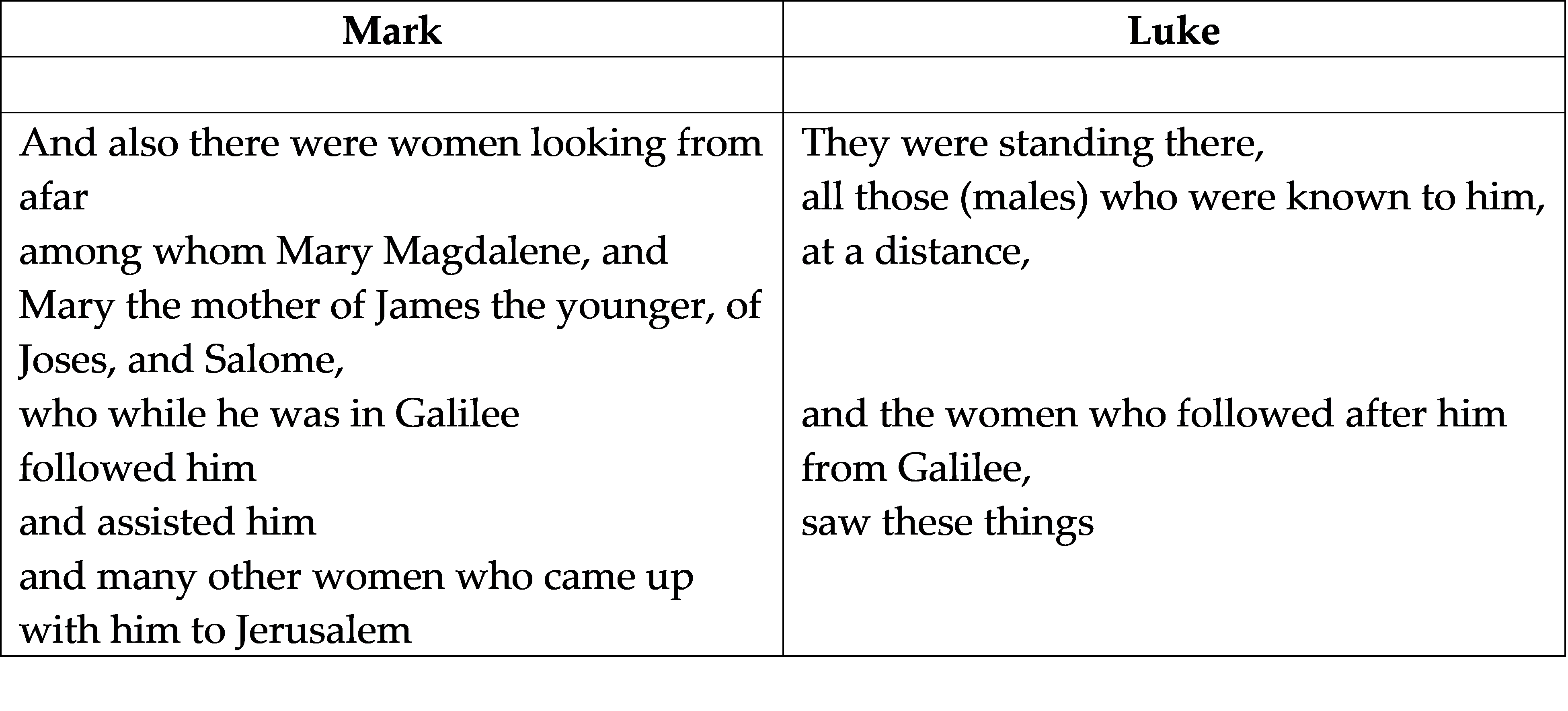

The Gospel attributed to Luke depends on the Gospel attributed to Mark for Jesus’ execution and burial, and the empty tomb narratives. In the author’s editing of the Marcan narrative, the women’s names, their particularity, disappear and they are subordinated to a male group of his acquaintances—literally “those males known to him.” English translations play the male aspect down with the neutral “acquaintances." But the Greek is not neutral but clearly male. The construction of Mark’s Greek had accented the women’s role, no males present; Luke’s editing diminished and hid their role, even their existence.

Mark’s sentence (in Greek, a period) is carefully balanced. The women followed him while his was in Galilee, which means that they too were disciples/students. They also “assisted him.” The Greek diēkounoun from which the English word “deacon” is a transliteration has a strong liturgical or ritual sense. All this careful construction is completely obliterated in Luke. The women go unnamed and are subordinated to the men.

At the conclusion of the burial narrative, in Mark the narrator notes once more the names of the women, but Luke again eliminates the names. “The women who had come with him from Galilee followed. They kept an eye on the tomb, to see how his body was laid to rest” (Luke 23:55).

Finally, at the beginning of the empty tomb narrative in Luke, the women again are not named, as they are in Mark. Their presence is reduced to three verbs whose subject is implied from their previous mention at the conclusion of the burial story. “[They] came to the tomb, . . . and found the stone rolled away and entering it found not the body of the master Jesus” (24:1–3, my translation).

When they return from the tomb, they report to the Eleven (24:9). This clearly subordinates the women to the Eleven, a male group. The narrator does not inform the reader where they are. The Upper Room is an invention of the Fourth Gospel. Also, at Jesus’ arrest, the disciples do not flee (see Mark 14:40—no Lucan parallel). Their absence to this point is unexplained.

Only after they report to the Eleven does the narrator note, “The group included Mary of Magdala and Joanna and Mary the mother of James, and the rest of the women companions” (24:10). These other “women companions” have been absent since Jesus’ execution. Now they reappear. The narrator continues, “They related their story to the apostles; but their story seemed nonsense to them, so they refused to believe the women” (24:10–11). In Luke the Eleven, the Twelve before Jesus’ execution, and the apostles are the same group. That is unclear in Mark. For Paul, the Twelve and the apostles are two separate groups (see 1 Cor 15:5, 7). But the Eleven apostles dismiss the women’s witness as “nonsense.” The Greek word is widely used to denote triviality, trifle, nonsense, chatter. It is a dismissive word. The narrative views the women as chattering women talking nonsense. The named women who are the source of the tradition in Mark are rejected in Luke. History and patriarchy preferred Luke’s model.

The long and unique story of Jesus appearing to the two travelers on the way to Emmaus follows the rejection of the women’s story. Following the breaking of the bread with Jesus and his disappearance, these two go to find the Eleven and report to them what has happened. But before they can get their story out, the Eleven report “The Master really has been raised and has appeared to Simon!” (24:34). This is Pauline language (see 1 Cor 15:5).

The author of Luke needs to neutralize Mark’s story, which makes the women the only witness to Jesus’ death, burial, and resurrection. This author follows the Pauline tradition, which makes Cephas the first witness (1 Cor 15:5). The Gospel attributed Luke establishes Peter’s primacy and apostolic tradition derived from the Twelve Apostles. The author did this at the women’s expense. Matthew may have given the keys of the kingdom to Peter, but Luke established Petrine primacy.

We can also draw another conclusion. The author of Luke’s Gospel does not know a story of a resurrection appearance to Peter. The author only knows Paul’s statement: “he appeared to Cephas, and then to the Twelve” (1 Cor 15:5), although he corrected Paul’s Twelve to the Eleven, accounting for Judas’ death.

Finally, Luke’s Gospel starts down the road to Mary Magdalene losing her reputation. Mark abruptly introduces the women after the centurion’s declaration. Narratively this makes little sense. If they had followed Jesus in Galilee, why no mention of them before?

The author of Luke’s Gospel knows nothing about Mary Magdalene other than what appears in Mark’s Gospel. But the author radically rearranges how Mary Magdalene appears in the gospel narrative. Mary Magdalene first appears at Luke 8:2, early in the narrative, rather than later at the crucifixion as in Mark. Early in Jesus’ Galilean travels, the narrator notes that along with the Twelve were:

some women whom he had cured of evil spirits and diseases: Mary, the one from Magdala, from whom seven demons had departed, and Joanna, the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward, and Susanna, and many other women, who provided for them out of their resources. (Luke 8:2–3)

This implies that all the women had demons cast out (in contrast to the Twelve, who are presumably demon free) and Mary Magdalene had seven demons. She is not only first on the list but has the most demons! The mention of the formerly possessed women follows the truly weird story of the prostitute who anoints Jesus’ feet with her tears and hair (7:36–50). The confluence of a story of a prostitute and Mary Magdalene with seven demons plays to a dark stereotype about women, sparks the Christian male imagination, and initiates the trashing of Mary Magdalene’s reputation. It marks the first step on the road to Pope Gregory’s proclamation in 591 CE.

She whom Luke calls the sinful woman, whom John calls Mary, we believe to be the Mary from whom seven devils were ejected according to Mark. . . .It is clear, brothers, that the woman previously used the unguent to perfume her flesh in forbidden acts. What she therefore displayed more scandalously, she was now offering to God in a more praiseworthy manner.

Only Luke’s Gospel pictures Mary as demon possessed, which is the first step in trashing her reputation. Gregory the Great’s proclamation demonstrates the danger of eisegesis (reading into), combined with the male gaze.

Ever since, the male gaze in the West has enthusiastically celebrated the papal fantasy.

Subscribe to our email list and receive updates, news, and more.

Join the Conversation in the Westar Public Square

We’re updating how we engage with your thoughtful feedback! Blog post comments will no longer be hosted on our website. Instead, members can join the conversation in the Westar Public Square, where blog post links will be shared for deeper discussions.

Not a member yet? Join us to connect with a vibrant community exploring progressive religious scholarship! Become a Member Today