In his discussion of slavery, Aristotle makes an important observation relevant to the current political situation. In determining whether slavery is natural, he remarks, “in some cases things are marked out from the moment of birth to rule or to be ruled.” By observing nature, looking at things as they are, Aristotle asserts that slavery is natural, a proven fact. Some are born to rule; others to be ruled. It’s that simple, common sense. Look around—that’s what you will see in all manner of things. The contemporary idiom “a born leader” underlines the continuing power of Aristotle’s common sense reflection.

That common sense observation has justified every form of hierarchy.

Make your own list.

An implication of “born to rule” is that the gods or God approve of and ordain the ruler. In this way rulers co-opt religion. Since God created the world, this is the way “He” meant it to be: some ruling, others ruled.

Aristotle’s common sense dictum is from the rulers’ point of view. They believe they are destined to rule. On the other hand, many, if not most of the ruled—the exact proportion is impossible to know—disagree. This makes all forms of authoritarian government inherently unstable. Religion, of course, has been a major counterbalance in stabilizing these governments, even to the present day. Karl Marx made precisely this point in his critique of religion as the “opium of the people.”

All authoritarian governments figure out ways to neutralize their inherent instability or they descend into chaos. The Roman Empire under Augustus developed a program of incorporating the land-owning class of conquered territories into its political sphere. It provided them with a path to Roman citizenship and left them in control of the local situation. By allowing home-grown elites to collect taxes and administer their own areas, the empire provided real incentives for the elites to take responsibility for the locals and at the same time drew them close to the empire. They became Romans as well as locals. This led to a prospering of local villages and cities and resulted in imperial control with a very small bureaucracy. The footprint of the Roman Empire was light on the ground for its enormous size. Once Augustus established the template, it remained in place for more than four hundred years.

The problem with arguing against common sense is that common sense does not think it needs an argument to justify its position. It’s common sense, the default. Everybody knows it. To refute common sense one needs critical thought and that is hard, out of the ordinary, by definition not common sense. You can be called names, egghead or worse.

In the first philosophy course I ever took, the professor began by remarking that philosophy will teach you to doubt and challenge common sense. Look at this chair, he said. Common sense tells you it is solid. Science tells you it is made of atoms. Philosophy will help you adjudicate between different claims. Since we were beginning philosophy students, he provided us with an overly simple example.

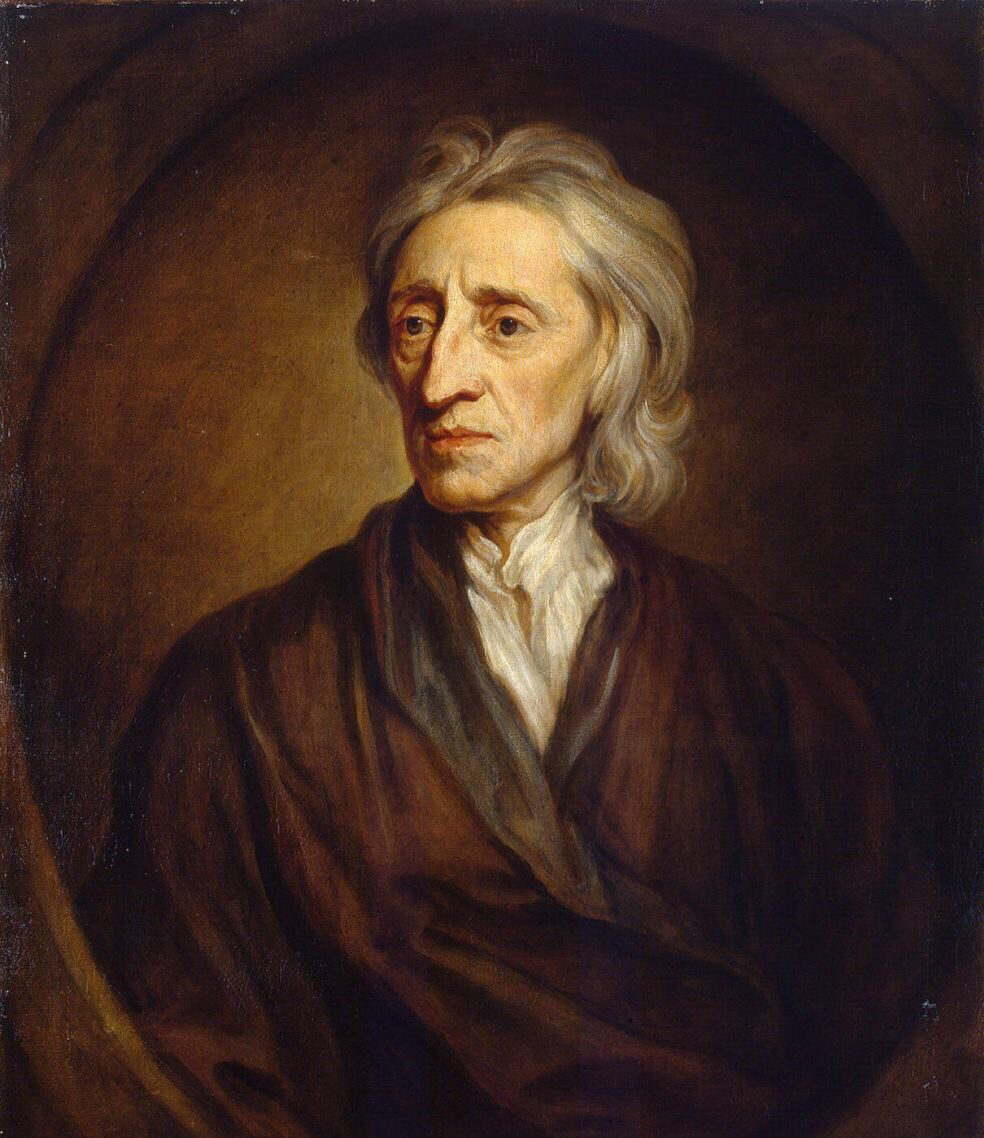

The attack on Aristotle’s common sense dictum “born to rule” came in the Enlightenment. The English philosopher John Locke in his Two Treatises of Government (1689) argued that all humans were equal.

The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions.

Both Aristotle and Locke base their understanding on the state of nature. Both agree that reason can understand what is natural, but Aristotle and Locke draw diametrically different conclusions. For Aristotle some are born to rule; for Locke all are equal. The reason for this difference is important to observe. Despite both Aristotle’s and Locke’s claim, the conclusion is not a deduction of reason but a matter of personal experience, even social location. Aristote sides with the ruler; Locke with the ruled. Ultimately, the argument is futile. It depends on how you see the world, your place in the world. This is why modern politics tend to divide between conservative (born to rule) and liberals (from the Latin liber, “free.” Everyone is free or equal).

Modern democracies are inherently unstable because of this tension between fundamentally opposed starting points. Rights and their understanding are expansive and corrosive. All men are created equal might at first apply only to white males, but others will soon see and claim that it applies to them—enslaved Africans, women, Native Americans, homosexuals, the list goes on and on. Those who believe they are born to rule, entitled to rule, will resist this expansion because it invades or corrodes their rights. William F. Buckley Jr., in a 1957 National Review editorial, made this argument in defense of White segregationists. White Southerners had a right to defend their civilization against the claims of Black Americans, whom Buckley called Negroes, because they represented, he said, an inferior culture.

Modern liberalism was born in the Enlightenment. Modern conservatism in the tradition of Edmund Burke (1730–1797) and Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821) began as a reaction to the violence of the French Revolution. They argued the rebels had taken freedom too far.

Liberalism’s duty is clear: to press for the expansion of rights and freedoms. Conservatism at its best acts as a check on liberalism’s expansion of rights if liberalism goes too far. At its worst, it attempts to block or even repeal the expansion of rights. Conservatism in recent years has been in reactionary mode, attempting to reverse the gains of African Americans and women and maybe even the New Deal.

The history of American democracy (demos [people] + arche [rule]) has explored and negotiated who are the people. Liberals and conservatives do not disagree on the need for rule, but on the definition of demos, the people. That negotiation is the tale of American history. Its flashpoint has always been those enslaved or formerly enslaved. The question is how those people are part of “We the People,” the demos of democracy.

We are still contesting that question. It may break out yet again in open warfare.

For my part, my bet is on freedom. Once glimpsed or tasted, it’s hard to give up. It is inspiring. Defending entitlement is not.

Subscribe to our email list and receive updates, news, and more.

Join the Conversation in the Westar Public Square

We’re updating how we engage with your thoughtful feedback! Blog post comments will no longer be hosted on our website. Instead, members can join the conversation in the Westar Public Square, where blog post links will be shared for deeper discussions.

Not a member yet? Join us to connect with a vibrant community exploring progressive religious scholarship! Become a Member Today